By Lulu Yilun Chen and Yuji Nakamura

(Bloomberg) --Here’s another reason to be leery of the initial coin offerings being done at a staggering pace in the cryptocurrency world: there’s a one-in-10 chance you’ll end up a victim of theft.

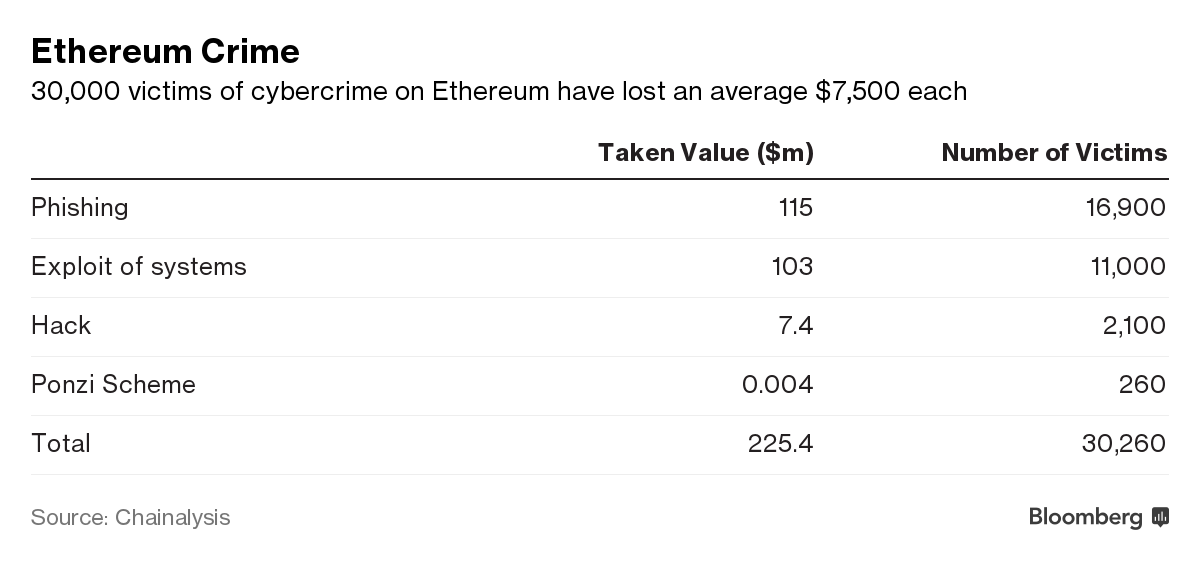

Phishing scams have helped push up criminal losses to about $225 million this year, according to Chainalysis, a New York-based firm that analyzes transactions and provides anti-money laundering software. In such scams, investors are tricked into sending money to internet addresses pretending to be funding sites for digital token offerings related to the ethereum blockchain technology.

More than 30,000 people have fallen prey to ethereum-related cyber crime, losing an average of $7,500 each, with ICOs amassing about $1.6 billion in proceeds this year, Chainalysis estimates.

“It’s a huge amount of money to generate in such a short period of time,” said Jonathan Levin, co-founder of Chainalysis, whose software and database are used by some of the largest bitcoin companies and U.S. law enforcement agencies. “The cryptocurrency phishers are doing pretty good against all the other types of criminals that are out there.”

Indeed, the huge amount of wealth that has fallen prey to cyber criminals is approaching the losses incurred by robberies in the U.S. for the entire year of 2015, which stood at $390 million, according to statistics released by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

ICOs are digital token sales typically that raise ether, with users transferring the funds to addresses provided by startups. Investors, sometimes eager to get early access to new token offerings have been tricked into providing their credentials to fake websites through targeted email campaigns, twitter posts and Slack messages, said Levin.

Ether rose 0.3 percent to $324.92 on Thursday, according to data from coindesk, while bitcoin rose 0.4 percent to $4,151.47.

Most attacks involve creating websites or social media accounts that sound similar to the real ICO project. Levin gave the fictional example of a project named "illuminate," which an imposter might fake by spelling it as "iIIuminate." Using the fake account, they would solicit potential investors to send money to the criminal’s address.

His firm compiled the data by identifying so-called digital wallets used by scam artists. That information is usually public because criminals widely circulate it, hoping to fool investors into sending them money.

Other common forms of crime involve tapping into project loopholes. The DAO, or decentralized autonomous organization, is a smart contract project built on top of ethereum that was intended to democratize how ethereum projects are funded. A bug in the system was exploited and that led to the theft of $55 million worth of ether at the time.

Levin didn’t provide data for bitcoin-related cybercrime, and not because it is any safer. He said such data is harder to track as scams are usually specific attacks on individual holders, rather than ICO-related campaigns which try to dupe many people at once.

“The overall figures mean there are infrastructure that we need to build to help prevent people from getting abused,” said Levin.

To contact the reporters on this story: Lulu Yilun Chen in Hong Kong at [email protected] ;Yuji Nakamura in Tokyo at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Robert Fenner at [email protected] Dave Liedtka