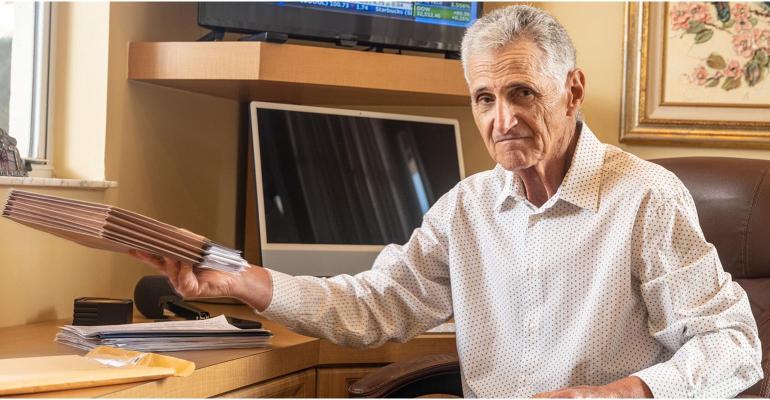

(Bloomberg) -- Thanks to the persistence of Larry Wasserman, a 78-year-old retired broker who lives in Boca Raton, Florida, about 300 investors who were overcharged for municipal bonds are getting $3.4 million back.

Wasserman, who retired in 2016 after almost five decades, discovered that a key data point known as a factor had been improperly calculated on a bond he had purchased. The figure is a rare feature in muni bonds, and the steps that he had to go through to figure out he had overpaid underscore how opaque the $4 trillion tax-free debt market can be for individual investors.

The former broker made more than 20 calls to the trustee of the bonds and the company that insured them to straighten out the trouble with the factor. He compiled enough information to call regulators, which investigated and determined that he and others had been overcharged.

“Without that call, it would’ve been below the radar,” said Richard Laufer, a specialist manager at the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. “The likelihood of this being identified was small.”

Wasserman’s odyssey began in November 2017, when he bought a “capital appreciation bond” with a $75,000 face amount issued by the Santa Rosa Bay Bridge Authority. CABs are similar to zero coupon bonds, which are sold at a price below face value, and pay out at 100 cents on the dollar plus accrued interest upon maturity.

While factors are common in the mortgage backed securities market, where the figure generally moves down over time as homeowners pay down principal, they’re rare in the muni market. Out of 900,000 municipal bonds outstanding, fewer than 1,000 include a factor, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The Santa Rosa bonds traded with a factor because in 2011 the bridge didn’t generate enough revenue and defaulted on bonds that had conventional coupon payments due. Traffic on the Garcon Point Bridge — the two-lane toll bridge on the Florida panhandle near Pensacola — that was financed by the debt, had fallen short of projections.

That default entitled holders of the CABs to get their principal back sooner than previously expected, under a process known as acceleration, beginning in 2013, according to a securities filing. Toll revenue that was left over after paying for the bridge’s operations would be returned to bondholders, including those holding CABs.

When Wasserman bought the Santa Rosa bond, the factor was 0.8676, meaning about 87% of the principal was still to be repaid, or around $65,000 for Wasserman. The factor is provided to brokers by data vendors, who determine the figure based on information from the bonds’ trustee.

Some months later, when Wasserman was reviewing his brokerage statement, something caught his attention. Even though he was receiving some principal payments, the factor on his statement didn’t change.

“I was suspicious,” said Wasserman in a telephone interview.

Overstated Factor

He started investigating. Unlike most individual investors in the muni market, Wasserman was familiar with factors because of his long career in the brokerage business. His forte was in munis but he sold every product, including agency mortgage backed securities that use factors.

After noticing the static factor on his statement, Wasserman asked his brokerage firm, whom he declined to identify, about it. The firm told him they didn’t set the factor.

He then called UMB Bank, the trustee on the bonds, and National Public Finance Guarantee, which insured his securities. Both sent copies of the factor schedule, which showed that in November 2017, when he bought the bonds, the figure was not 0.8676, but 0.5598.

There was less principal remaining to be paid back than he had thought at the time. He had overpaid.

In late summer 2020, when he opened his brokerage statement, Wasserman saw that the factor had dropped, but he hadn’t received any offsetting payments.

“That should have been enough for [his brokerage] to understand something went wrong there, but they refused to believe it,” Wasserman said.

Knowing he was on to something, Wasserman called Finra’s senior helpline in February 2021, asked them to investigate and sent supporting documents, according to the regulator. (Wasserman himself said he first called Finra in 2020.)

“He was a great investigator,” said Finra’s Laufer. “He did his research.”

Citi, MS

Wasserman had a leg up in looking into this issue because of his career. He grew up in Schenectady, New York, the son of a meat wholesaler and retailer. He moved to Florida in 1965 to attend the University of Miami, where he studied economics.

In 1970, he started his career at duPont Glore Forgan Inc, followed by a series of firms including more than three years at EF Hutton & Co., 15 years at what is now Citigroup Global Markets, and six at Morgan Stanley.

Laufer and his team analyzed periodic distribution notices filed by the trustee that showed how much principal was returned to bondholders and calculated the correct factors for the Santa Rosa bonds. Finra contacted Wasserman’s broker, which agreed to repay him $24,000.

The regulator then analyzed Santa Rosa bond trades from 2013 through 2021 and found that the application of the inaccurate factor was a widespread problem, but not intentional. Finra contacted 30 brokerage firms that sold Santa Rosa bonds who agreed to reimburse the customers.

“The firms were relying on their vendors and the vendors got it wrong,” Laufer said. “There’s just not a consistent process across the muni industry for communication of a factor.”