In his long career, Vanguard founder Jack Bogle has given many speeches championing passive investing. After the talks, audience members have often asked a troubling question: What happens if everyone invests in index funds? The questioners worried that the markets would no longer function if too many investors bought and held the same baskets of stocks. For years, Bogle has brushed aside the issue, saying that index funds will always account for a small percentage of total invested assets.

But these days the picture has changed. According to Morningstar, passive portfolios hold 22 percent of fund assets, up from 11 percent in 1999. Now it is no longer possible to ignore the impact of indexing. With money pouring into index funds and ETFs, passive portfolios are distorting markets, harming many investors. Index funds are creating disturbing conditions in a variety of asset classes, including emerging markets, small stocks, and commodities.

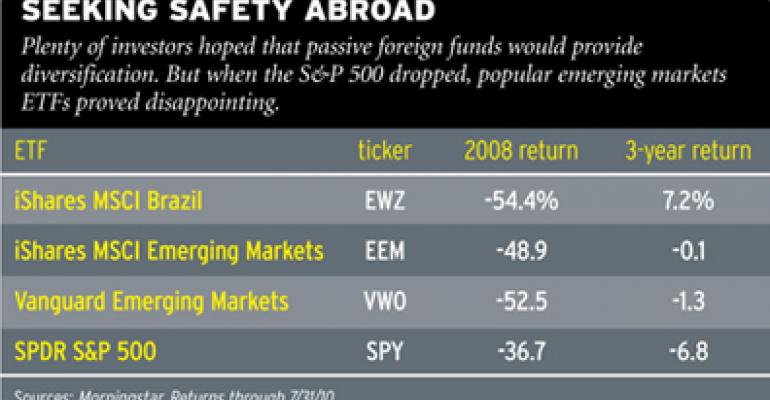

Emerging Markets

In the past, passive funds played little role in the emerging markets. But that has changed dramatically in the last several years. Consider Brazil. With $9.6 billion of assets, iShares MSCI Brazil ETF (EWZ) now accounts for about 1 percent of the market capitalization of the Brazilian BOVESPA exchange. Two other ETFs, iShares MSCI Emerging Markets (EEM) and Vanguard Emerging Markets (VWO), together hold more than $10 billion in assets in Brazil.

Although they account for a fraction of Brazilian assets, the three funds are responsible for 50 percent of all the trading in Brazilian shares, says Scott Burns, Morningstar’s director of ETF research. The ETFs have such a big impact because investors trade them heavily.

The influence of the passive funds was especially pronounced during the downturn of 2008. In a year when the S&P 500 lost 37.0 percent, iShares MSCI Brazil dropped 54.4 percent. The big decline occurred even though the Brazilian economy remained fundamentally sound. Morningstar’s Burns says that Latin American markets plummeted because panicked investors in the U.S. were dumping ETFs of all kinds. Emerging markets funds failed to provide the kind of diversification that many investors expected. “As passive investing has grown, the correlations of the emerging markets and the U.S. have increased,” says Burns.

Commodities

Seeking diversification, investors have been racing into ETFs and separate accounts that track commodity benchmarks. But most investors have been disappointed, receiving weak returns and little diversification. To appreciate the problem, consider United States Oil (USO), an ETF that tracks the price of a barrel of crude. During 2009, oil doubled, climbing from $33 a barrel to more than $66. But the oil ETF only returned 18.7 percent for the year.

The disappointing result can be traced to how United States Oil is structured. The oil ETF holds futures instead of actual barrels of crude. Each month the portfolio managers buy one-month futures contracts, which represent bets on the future price of oil. Near the end of the month, the managers sell the contracts and buy new one-month futures. The problem is that many other portfolio managers are making exactly the same trades. As a result, the price of futures is depressed during times when all the managers are selling. Prices become inflated when many managers all try to buy the same contracts at once. That lowers returns.

In some cases, a manager might sell a contract for $50 and then be forced to pay $60 for a new contract. Traders call this situation contango. Because of contango, ETFs deliver skimpy returns when commodity prices are rising. When prices are flat, the ETFs tend to record losses. Scott Burns says that he has stopped recommending commodity ETFs that invest in futures. “I would not buy commodity ETFs until we get out of this persistent contango,” he says.

Large-Cap Stocks

After Google (GOOG) announced recently that it was being added to the S&P 500, the stock jumped 8 percent. The move was hardly surprising. Stocks nearly always enjoy a bounce when they join a benchmark. The movements occur because whenever a stock enters an index, many passive portfolio managers must rush to buy the shares. When a company is booted from an index, the shares usually sink as passive funds dump the stock.

Besides distorting prices of shares, the growth of passive funds may be contributing to the bubbles that have swept the markets during the past decade. The problem can be traced to the way that stocks are commonly weighted according to market capitalization. Under the system, big stocks count for more weighting. The largest stock in the S&P 500 is Exxon Mobil (XOM), which accounts for 3.2 percent of assets in the benchmark. Some of the smallest stocks only account for 0.01 percent.

Periodically a handful of big stocks catch fire and account for a growing percentage of index assets. Then as more cash flows into S&P 500 funds, a bigger share of the new money goes to buy a limited number of winning stocks. In the 1990s, cash flowing to index funds fed the rise of technology stocks. Before the credit crisis began in 2007, passive investors pumped cash into financial stocks. After the bubbles burst, shareholders were left to wonder why the market rose and fell so dramatically.

Small-Cap Stocks

The distortions can be especially severe for the small stocks of the Russell 2000 index. Each June Russell reconstitutes it benchmarks, adding some stocks and eliminating others. The 1,000 largest stocks go into the Russell 1000 index and the next 2,000 become the Russell 2000. Several months before Russell announces the annual changes, hedge funds and other speculators compile lists of candidates that seem likely to enter the Russell 2000. The speculators buy the stocks ahead of time, a process that pumps up share prices.

Because of all the speculative trading, the Russell 2000 obtains new stocks at high prices. That depresses the benchmark’s returns by up to 2 percent a year, says Peter Jankovskis, co-chief investment officer of Oakbrook Investments, a registered investment advisor in Lisle, Illinois.

How should you cope with all the market distortions? Jankovskis says that investors should rely on actively managed funds that pick and chose undervalued stocks. “For our small-cap holdings, we don’t just own the Russell 2000 because that pool of assets suffers from a permanent handicap,” he says.