Two decades ago load funds represented a huge business for advisors. In a typical transaction, a client paid an up-front load of 5 percent to purchase Class A shares of a fund. Major fund companies that relied almost exclusively on load sales included Franklin, Putnam, and American Funds. In the early 2000s, fund companies rolled out even more load offerings. But then the business began to change. Instead of charging sales commissions for each transaction, more firms shifted to advisory models, charging annual fees of 1 percent or so. Sales of load shares slipped, replaced by no loads or funds that waived loads.

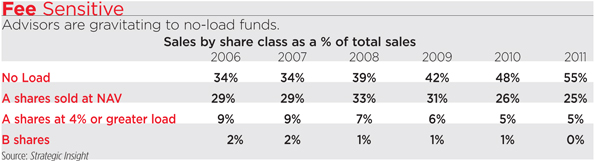

In recent years, the transition away from loads has accelerated. In 2006, shares without loads accounted for 63 percent of all fund sales recorded by advisors, according to Strategic Insight. By 2011, the figure had increased to 80 percent. Will the move away from loads and commissions continue? Yes, says Avi Nachmany, research director of Strategic Insight. “The old commission business is fast disappearing,” says Nachmany.

In short, with the fast rise of the ETF, investors have clearly got fees on their minds—of course markets of 2008-2009 will do that to a retail investor.

Endangered Species?

Not everyone is convinced that loads will vanish entirely. Some advisors continue to rely on load sales. At Edward Jones, load shares account for a bit more than half of all fund sales, says Greg Dosmann, a principal with the firm. Dosmann says that in many cases, load shares are the cheapest alternative. “Our aim is to provide the share class that is best for a specific client,” he says.

Dosmann cites an example where load shares make sense. Say a client plans to own a fund for 10 or 20 years. Instead of paying an annual 1 percent fee, it would be cheaper to buy A shares with a one-time front-end load. The A shares are especially attractive for clients with large accounts. In a typical A share structure, clients with less than $50,000 to invest in a fund must pay a front-end load of 5 percent to 5.75 percent. But the fee is lowered to 3.5 percent to 4.5 percent for $100,000 investments. Clients who invest $1 million pay no load at all.

At Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, no-load sales have become more important, but the load shares still account for 35 percent of new fund sales, says managing director Paul Weisenfeld. He says that some clients prefer holding both load and no-load funds. To illustrate why, he cites his own portfolio. His no-load assets are in an account that is overseen by an advisor who has discretion over the investments and charges an annual fee. “She does an awesome job managing the portfolio, and I don’t want her to call me every time there is a trade,” he says.

In a second account, he plays a role in making decisions. The portfolio includes buy-and-hold choices, such as Morgan Stanley stock, municipals bonds, and load mutual funds. “I don’t need much help to manage the funds and Morgan Stanley stock,” he says.

Drawing Regulatory Interest

In recent years, regulators have focused attention on loads and other methods that are used to compensate advisors for fund sales. Former SEC chairman Mary Schapiro railed against 12b-1 fees and called for reducing them. The move provoked concern in the industry because the change could cut the incomes of many advisors. In a typical arrangement, a broker who sold Class A shares could collect annual 12b-1 fees of 0.25 percent or more. According to the Investment Company Institute, the fund trade group, 12b-1 fees produced $13 billion in revenues in 2007.

But the SEC has backed off its calls for reforms. The commissioners have become less insistent about fees partly because Washington has been distracted by other matters, such as the drive to change money markets. In addition, the amount of 12b-1 fees has dropped sharply as the structure of fund shares has changed. Load shares, which once charged steep 12b-1 fees, are disappearing. Some no-load shares have also been eliminating 12b-1 fees. According to Strategic Insight, 13 percent of no-load funds in wrap-fee programs had 12b-1 fees in 2011, down from 28 percent in 2009. “A few years from now, 12b-1 fees will be a minor factor,” predicts Avi Nachmany.

Besides fretting about 12b-1 fees in recent years, regulators also focused on B class shares, which charge a back-end commission that is imposed at the time of a sale. In a typical arrangement, investors who sell the fund within a year of purchase may face a 5 percent commission on the sale. That load declines the longer the investor holds. In addition, B shares often charge steep 12b-1 fees.

Regulators worried that advisors were using B shares when other classes would be cheaper. In recent years, FINRA fined advisors who did not use the best share class. Worried about running afoul of regulators, advisors backed away from B shares. As recently as 2007, some companies continued selling the shares. But according to Strategic Insight, B shares now account for virtually none of the new sales.

The shifts in share class have been particularly pronounced at American Funds, the largest advisor-sold fund company with $915 billion in assets. For decades, American prospered by selling primarily A shares to clients who held for the long term. The company also offered B and C shares, which charge annual fees of around 1 percent. Then in 2009, American stopped offering B shares. To accommodate fee-only advisors, the company has introduced some new share classes. The F-1 class comes with 12b-1 fees, while F-2 shares do not impose 12b-1 charges. Investors who buy the F-1 shares of American Funds Growth Fund of America (GFAFX) face a 12b-1 fee of 0.25 percent and a net expense ratio of 0.68 percent. The F-2 version only costs 0.44 percent.

The A shares remain popular choices at American Funds, but many clients are in wrap fee programs where the load charges are waived. Investors make their purchases for the net asset value of the funds. “As advisors migrate to asset allocation models, we are seeing more clients buy A shares at the NAVs,” says Antonio Ferreira, managing director of Cogent Research.

In the new world of fee-only accounts, many advisors are drifting away from the actively managed funds offered by American Funds and other companies and shifting to ETFs and index funds. But Ferreira argues that American Funds can prosper in an environment where load funds no longer play a big role. “Advisors are adjusting to new fee structures, and they still have confidence in the stability and long-term performance of American Funds,” he says.