With stocks rising in 2006, Legend Financial Advisors began shifting the asset allocations of clients. Fearing that real estate prices had gotten too rich, the Pittsburgh firm sold all its real estate mutual funds. Then as equity markets continued climbing in 2007, the firm eliminated all its domestic equity funds, putting assets in long-short funds and other choices that can, in theory, hold up better in declining markets.

The strategy worked beautifully to limit losses in last year's vicious downturn. “In this kind of difficult market, you need something other than a standard allocation to stocks, bonds, and cash,” says Diane Pearson, an advisor with Legend, a registered investment advisor that clears trades through TD Ameritrade. “How many clients would we have left if we let them lose half their assets?”

Good valuation calls by Legend, eh? How often have you junked your traditional asset allocation models to make a market timing call, chucking a whole asset class because you think it's overvalued? It's heresy, really. But last year, you would have prospered. Few asset classes worked last year (apart from going long the dollar and Treasuries, cash was just about it), calling into question traditional views on asset allocation. Badly embarrassed by client losses, many advisors now say that portfolios must be flexible and must be adjusted to shifts in financial conditions and valuations. (Sounds like what we used to call, pejoratively, “market timing.”) To be sure, the revisionists are in a distinct minority. Most advisors and money managers remain loyal to the standard approaches. As they have done for years, mainstream advisors still intend to put a certain percentage of assets in stocks — and hold the position for the long term. But at a time when many clients complain that asset allocation offered little protection last year, advisors may have reason to rethink their time-tested approaches.

Eggs In Several Baskets

Much of the traditional strategy dates to work done in the 1950s by Harry Markowitz, the father of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). Markowitz said that proper diversification could maximize expected returns while limiting risk. Embracing the ideas of Markowitz, institutional investors began adopting strategic allocation plans. In a typical approach, a pension fund would put 60 percent of its assets in equities and 40 percent in fixed income, rebalancing to keep the allocation constant.

Under most circumstances, static allocations have worked brilliantly. As Markowitz envisioned, some asset classes rose while others fell. That helped to give investors a relatively smooth ride. But in 2008, the approach failed, since nearly all asset classes collapsed at the same time. Conceding that diversification doesn't always provide protection in downturns, defenders of the standard thinking argue that the Markowitz approach offers the best way to protect assets over the long term.

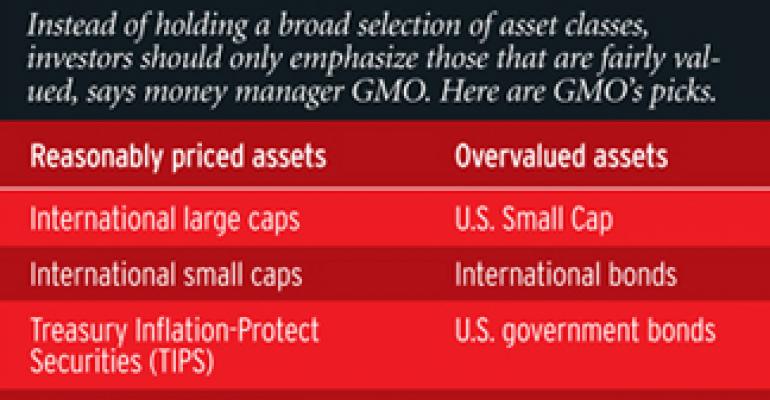

One of the most notable dissenters from the traditional thinking is GMO, the Boston money manager run by the legendary Jeremy Grantham. GMO employs a system it calls dynamic asset allocation. In the approach, managers emphasize undervalued assets, shifting allocations as bargains appear.

Ben Inker, GMO's director of asset allocation, argues that investors put too much faith in the standard diversification approach. “Diversification sometimes works, but you can do even better by throwing out asset classes that are egregiously overvalued,” he says.

Inker says that confidence in traditional diversification soared after the market downturn that began in 2000. While growth stocks collapsed, REITs and small value shares rose. Private equity and hedge funds also proved resilient. Portfolios that included some of the rising assets outperformed the S&P 500 by a wide margin during the downturn. Seeing the results, institutional investors concluded that diversification could cushion portfolios in downturns.

Inker argues that the institutions drew the wrong conclusions about the collapse of 2000. Diversification appeared to work that year only because of peculiar circumstances. Going into the downturn, growth stocks were overvalued, but asset classes such as real estate and small value stocks were undervalued. What followed was a massive correction. While overvalued stocks fell, bargain-priced assets climbed.

Last year diversification didn't work because nearly every asset class was overvalued, says Inker. “In 2008, the market came back to a semblance of reasonable valuations after a period when valuations were way too high,” he says. “If most assets are uniformly overvalued, then diversification among the assets isn't going to help.”

While GMO has produced strong long-term results, its strategy sometimes requires patience. With the bull market roaring in 1998, the money manager began shifting out of large growth stocks. By selling some of the market favorites, GMO looked foolish and missed opportunities for big short-term returns. But the move began to look shrewd when large growth stocks collapsed in 2000, and GMO clients avoided much of the damage.

What is GMO buying now? The money manager is overweight in high-quality U.S. stocks and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). It has no REITs and is underweight emerging markets.

Annuities? Yes, Annuities

While GMO limited losses last year by avoiding overpriced assets, other advisors have been lowering volatility by putting a new emphasis on annuities. In a typical strategy, an advisor calculates how much income a client needs in retirement for necessities, such as rent. The client then uses part of his nest egg to buy an immediate annuity that will provide enough lifetime income to cover basic expenses. The rest of the assets can go into a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. That way the retired client will not be evicted from his home, even if stocks collapse.

Having experienced last year's frightening downturn, more clients will be open to using annuities, says Tim Noonan, managing director of client services for financial advisor Russell Investments. “We learned last year that market risk was far greater than what the typical investor could stand,” Noonan says. “To provide more stability, there is going to be a lot more use of annuitization in the future.”

By holding both annuities and conventional mutual funds, an investor enjoys some important flexibility. If markets crash, a retiree can derive income from annuities, postponing withdrawals from stocks until they rebound. During a bull market, the retiree may sell stocks for income and delay buying an annuity. That could result in higher annual income, since the cost of obtaining lifetime income decreases as the investor ages.

So far most advisors are not rushing to buy annuities. Instead, they are sticking with conventional mixes of stocks and bonds. But even traditionalists recognize that strategies may need to be adjusted. Over the years, the success of diversification rested on the idea that not all investments moved in lockstep. While some assets have high correlations with the S&P 500, others move in different directions.

In an increasingly global economy, the value of diversification has declined as correlations have increased. “There is more global correlation as more information is put into the marketplace at faster rates,” says John Thompson, a portfolio manager with Ibbotson Associates.

Thompson argues that it is still important to diversify. But he concedes that as Internet use continues growing, correlations may keep rising — and the protection offered by diversification could continue to decline.