It’s said that politics begets strange bedfellows, but politics ain’t got nuthin’ on the oil bidness.

Case in point: Delta Airlines (NYSE: DAL) is hooking up with Phillips 66 (NYSE: PSX), the downstream operation recently spun off from oil giant ConocoPhillips (NYSE: COP). More specifically, the Atlanta-based air carrier’s wholly owned Monroe Energy subsidiary bought an idled Trainer, Pa. refinery from Phillips as a hedge against rising jet fuel costs. By Delta’s reckoning, the purchase could end up saving the company $300 million a year.

To be sure, fuel is the single biggest expense in the airline industry. Delta burned 3.9 billion gallons of the stuff last year, at an average cost of $3.03 a gallon. That $11.8 billion represented 36 percent of the carrier’s operating expenses. But, while fuel costs have spiked nearly 90 percent over the past three years, go-juice is actually cheaper than it was a year ago. In this environment, you have to wonder why Delta doesn’t just hedge with more conventional forward contracting when necessary. Does Delta know something other airlines don’t?

To answer that, we first need to know more about Delta’s deal. The carrier is paying $150 million for the 185,000 barrel-per-day refinery plus another $100 million for equipment upgrades. As an offset, Delta gets $30 million in state infrastructure and job creation subsidies, reducing its net investment to $220 million. The refinery purchase, according to Delta officials, approximates the cost of a single wide-bodied jet. Seemingly, the airline could recoup its costs in just one full year of refinery operations.

But how? After all, jet fuel isn’t a refinery’s primary output. More gasoline is typically produced by these facilities than any other distillate. Indeed, before operations were suspended last fall, the Trainer refinery’s output was 52 percent gasoline. Only 14 percent of daily production was jet fuel, with the balance coming out as a mix of diesel, heating oil and other products. Not surprising, then, that the plant was struggling under its previous ownership as gasoline consumption dipped and costs for light oil grades—favored for gasoline production—spiked.

After Delta’s upgrades, the refinery will more than double its jet fuel productivity to 32 percent and cut back its output of gasoline to 43 percent. Stepping up jet fuel production alone won’t give the airline a free fuel ride, though. Delta’s struck a three-year agreement with BP (NYSE: BP) for input crude but the airline will be obliged to buy its oil at world market (read: notoriously volatile) prices.

Delta’s thirst for jet fuel won’t be slaked directly by its own refining either. The company will exchange its gasoline, diesel and other refining outputs for additional jet fuel from BP, ConocoPhillips and other sources. Officials claim this refining/swap combo should cover 80 percent of the carrier’s domestic fuel needs.

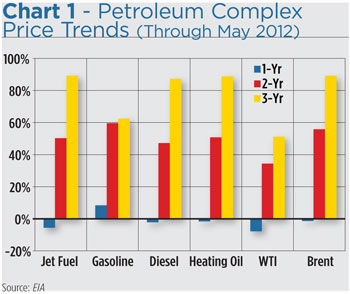

Delta points to the steep trajectory of jet fuel costs—versus that of crude oil—as justification for its refinery purchase. But the airline’s argument only holds water, er, fuel, if it benchmarks the light, sweet crude known as West Texas Intermediate, or WTI, in its calculation. Over the last three years, WTI spot prices have risen by 51 percent—a modest increase compared to the hike in Brent crude—the grade most often sourced by East Coast refineries like the Trainer facility. Brent’s prices have, in fact, moved in lockstep with jet fuel. (Chart 1 depicts the recent price trends of refined products and crude inputs.) If BP supplies crude to the Delta operation, input prices will likely be pegged at or very near Brent, so it’s hard to see where the savings arise.

Delta points to the steep trajectory of jet fuel costs—versus that of crude oil—as justification for its refinery purchase. But the airline’s argument only holds water, er, fuel, if it benchmarks the light, sweet crude known as West Texas Intermediate, or WTI, in its calculation. Over the last three years, WTI spot prices have risen by 51 percent—a modest increase compared to the hike in Brent crude—the grade most often sourced by East Coast refineries like the Trainer facility. Brent’s prices have, in fact, moved in lockstep with jet fuel. (Chart 1 depicts the recent price trends of refined products and crude inputs.) If BP supplies crude to the Delta operation, input prices will likely be pegged at or very near Brent, so it’s hard to see where the savings arise.

But here’s the real hitch: Jet fuel is typically more expensive than most other refined products. Delta’s construct of fast-paced increases in jet fuel prices translates into the trading of lower-priced products for a higher-priced commodity. Buying high and selling low is not a recipe for savings, either.

The savings Delta hopes to realize will ultimately be driven by what’s known as the “crack spread”—the difference between the barrel price of crude and the sale proceeds of refined products. Crack spreads vacillate for a number of reasons. First, there’s seasonality. Heating oil, for example, tends to move to a premium over gasoline in winter and early spring, but generally loses ground to trade at a discount in the summer driving season. More importantly, spreads are predicated upon a refinery’s equipment, product mix and target market.

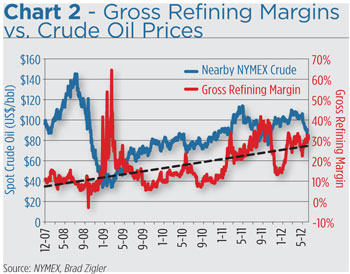

It’s the crack spread that determines an operator’s gross refining margin (GRM). Oddly, GRMs have actually been on an uptrend recently, albeit raggedly. Throughout 2009 and 2010, gross margins averaged less than 15 percent, but the numbers significantly improved in 2011 and 2012. Margins are now on the better side of 28 percent. (See Chart 2.)

Why, then, have so many refiners had such a hard time? To answer that, we have to first appreciate that margins are greatly dependent upon a refiner’s product mix.

Why, then, have so many refiners had such a hard time? To answer that, we have to first appreciate that margins are greatly dependent upon a refiner’s product mix.

The gross profit of refineries geared to crank out greater volumes of light distillates like gasoline can be roughly approximated by a “3-2-1 crack,” a refining scheme in which three barrels of crude oil yield two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of heating oil. (Motor and heating fuels are used as pricing benchmarks because they’re the most transparently priced and actively traded refined products.)

The proxy for refiners leaning toward middle distillates such as jet fuel, diesel and heating oil is a “2-1-1 crack” where two barrels of crude oil produce one barrel each of gasoline and heating oil. (Heating oil, diesel and jet fuel are chemically similar and are likewise comparably priced.)

Over the past year, refiners who tilted toward middle distillates earned 1.25 percent more on average than gasoline-heavy operations. That’s a telltale. Peaks and valleys in the margin differential often confirm broad economic trends.

3-2-1 runs tend to move to a premium over 2-1-1 operations in boom times and reverse to a  discount in downturns. When the economy's perking along, gasoline prices, reflecting consumer demand, rise faster than those of diesel and heating oil. Petrol consumption, in contrast, declines in bad times. (Corollary: Jet fuel pricing is most closely correlated to heating oil’s, so when heating oil is soft, an airline’s costs go down. It’s then that a carrier will want to stock up on fuel through forward contracting, even though demand for air travel may be relatively slack.)

discount in downturns. When the economy's perking along, gasoline prices, reflecting consumer demand, rise faster than those of diesel and heating oil. Petrol consumption, in contrast, declines in bad times. (Corollary: Jet fuel pricing is most closely correlated to heating oil’s, so when heating oil is soft, an airline’s costs go down. It’s then that a carrier will want to stock up on fuel through forward contracting, even though demand for air travel may be relatively slack.)

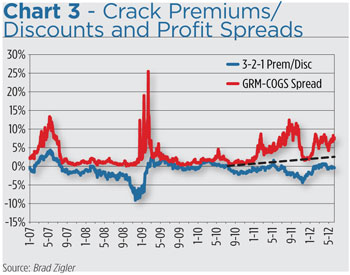

GRMs can tell us how much profit potential there is in a barrel of crude, but can’t be looked upon in isolation. To get a more complete picture of a refiner’s earning power, you have to compare its margin to the cost of goods sold, or COGS. The COGS is determined by dividing the refiner’s crack spread by its product sales proceeds. The more daylight between the GRM and the COGS, the better. A refiner becomes truly flush—all else held equal—when its margin exceeds the COGS by five percentage points or more. Chart 3 tracks the spread between the industry’s GRM and COGS. Also depicted is the premium/discount of 3-2-1 operations vs. 2-1-1 cracks. Higher percentage values for both metrics signal better economic times.

Obviously, operating costs have to be factored in to get a clear picture of a refiner’s ability to turn a profit. Given the age of America’s refining infrastructure, that expense can reduce margins significantly. The Trainer plant, in particular, is one of the older and least efficient refineries—a circumstance that obliged its former owner to rely upon the most expensive grades of feedstock crude. Thus, Delta is compelled to retool the facility to accommodate its new product mix.

The refinery’s profitability might be enhanced if cheap crude oil from North Dakota’s Bakken shale field or WTI banked in Cushing, Okla., could be shipped in. Both grades are currently selling at a discount to Brent because they’re essentially landlocked. Without a pipeline to transport crude to Delta’s refinery, though, an expensive combination of barges, trains and trucks would need to be marshaled.

So does this refinery purchase really make Delta smarter than the other airlines? Well, there seems some desperation in Delta’s move. The airline negotiated the deal as oil prices spiked amid a flare-up of Iran nuclear controversy. If oil prices weaken, Delta’s money could be wasted.

Still, the airline picked the right time to shop for assets. Integrated energy firms have been anxious to unload their downstream businesses, even at fire sale prices. Delta, too, may be watching those telltale spreads as bellwethers of better economic times to come.

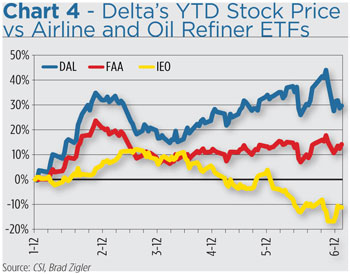

Investors apparently appreciate Delta’s chutzpah. The airline’s share price jumped 9 percent in the month after word of the refinery deal got out. Since then, the stock’s risen further, despite the overall market’s weakness. Two months after the purchase was publicized, Delta shares had risen 15 percent. On a year-to-date basis, the stock’s up 30 percent, far ahead of direct competitors United Continental Holdings (NYSE: UAL) and Southwest Airlines (NYSE: LUV).

That ought to make index followers green with envy. The Guggenheim Airline ETF (NYSE Arca: FAA), a portfolio of 26 global carriers’ stocks, is up just 14 percent on the year. Even more envious are those tracking the processing of black gold. Collectively, the value of the 60+ stocks held by the iShares Dow Jones U.S. Oil & Gas Exploration & Production Fund (NYSE Arca: IEO) have dipped 11 percent since the top of the year (see Chart 4).

That ought to make index followers green with envy. The Guggenheim Airline ETF (NYSE Arca: FAA), a portfolio of 26 global carriers’ stocks, is up just 14 percent on the year. Even more envious are those tracking the processing of black gold. Collectively, the value of the 60+ stocks held by the iShares Dow Jones U.S. Oil & Gas Exploration & Production Fund (NYSE Arca: IEO) have dipped 11 percent since the top of the year (see Chart 4).

Almost every U.S.-based airline has flown into bankruptcy at one time or another. When management isn’t blaming poor performance on high labor costs or weak business demand, fingers are pointed at rising fuel costs. Delta’s purchase just might stop some of that digital imputation.